Introduction

In this paper, I present two claims upon which my argument is based: First, that a large majority of the post-genocide media/artistic representation does not highlight/include Rwandan women, which leads to inaccuracies in global collective understandings of the Genocide. Second, Rwandan women played varying roles in the genocide, as different witness positions, and Hutu women were notably complicit in, or agents of, violence against Tutsi women, but many testimonies that do mention these women flatten them out into archetypes of helpless victims or scarred survivors, thus reducing their crucial role in Rwandan history and politics. Therefore, my argument is that there is insufficient (inaccurate and limited) representation of Rwandan women in globally circulated testimonies of the genocide, which leads to Historical Revisionism of the Tutsi Genocide, and perpetuates the Epistemicide of female African narratives. Raoul Peck’s 2005 film Sometimes in April, is the filmic depiction of the Genocide which this paper analyses, and Raymon Depardon’s 1999 photography collection RWANDA is an additional Genocidal depiction analysed. Both works are chosen for their critical acclaim and considerable success as Artistic Testimonies by Indirect witnesses, but, through engagement with scholarly works I will unpack the Victimological frameworks both artists employ in their portrayal of Rwandan women.

Theory of Revisionism and Concept of Victimology

This paper references several scholarly publications addressing artistic communication of genocide, role and reception of western audiences to filmic depictions of genocide, women’s roles in the Genocide and the post-Genocide political landscape, and how representation is a powerful tool for enacting social/cultural/political change, but one work is of particular note in this paper: Georgina Holmes’s 2013 book, Women and war in Rwanda: Gender, media and the representation of genocide. In her book, Holmes discusses the role of gendered narratives in Genocide, and how these narratives are then perpetuated by journalists and filmmakers, thus redirecting political discourse. These ideas are corroborated in this paper, but I focus specifically on her exploration of “the international politics of revisionism” (83); the rewriting of narratives around Rwandan women (via inaccurate/inadequate representation), which leads to erasure and changed interpretations of the Genocide, ultimately warping global collective understandings of the Genocide. She also explores the framework of “Victimology” (labelling individuals/groups of people as victims, and then only examining their experiences from the context of their victimisation) employed in discussions of Female Witnesses, another concept which is central to my argument.

In her introduction, Holmes states that she aims to “challenge normative readings about African women in conflict and in doing so resists the tendency to fit Rwandan and Congolese women into a framework of victimology which presents African women as silent, passive and lacking agency, so frequently – albeit often unwittingly – adopted by feminists theorizing international relations” (3), and in my paper, I strive to do the same.

Filmic Depiction of Rwandan Women

One of the most widely circulated and critically acclaimed fictional portrayals of the Genocide is the film Sometimes in April, which chronicles the differing experiences of two brothers prior to, during, and after the Genocide. The film is also renowned for its emotional accessibility to viewers, depicting how characters navigate the complexities of grief and guilt in a storyline that feels authentic to its context. Despite Peck’s work having considerable depth for a filmic portrayal of the Genocide, his representation of women is surface-level at best. To understand the significance of this inadequate representation, one must reflect upon its influence on Western perception via its wide outreach (as Western voices currently dictate most historical/political narratives). A quote from “Unearthing Ambiguities: Post-Genocide Justice in Raoul Peck’s Sometimes in April and the ICTR case Nahimana et al.”, an article by Anna Katila, PhD., helps to illuminate the film’s role as a representation of genocide, “Although there are numerous creative responses that portray the aftermath of genocide, including documentaries, plays, memoirs and novels, their reach and thus potential impact on the Western public perception are moderate in comparison to these films produced for mass consumption [...] examining commercial artworks by outsiders targeted at international Anglophone audiences can complement our understanding of the relationship between art and transitional justice” (Katila 334). Katila’s statement supports this paper’s claim that these slight insufficiencies in Peck’s representation of Rwandan women have snowball effects on Western and Global interpretations of the Genocide.

To further unpack Peck’s shortcomings in his communication of the female experience within the genocide, one can examine two secondary female characters: Augustin’s late wife, Jeanne, and his present partner, Martine. During the film, the audience comes to learn of the killings of Augustin’s wife and children, a moment of emotional impact on both him and the audience. This being said, the film strips away any nuance of Jeanne’s character by restricting her storyline to the context of her death, and only portraying her life in the context of her role as a wife and mother, thus resulting in audiences feeling greater sadness towards Augustin’s bereavement, than Jeanne’s violent death itself. Peck’s directorial choice to centre Jeanne’s narrative around Augustin and convey the tragedy of her death via his pain, results in implicit communication to his audiences that the injustice of a Rwandan woman’s death lay in the sorrow of the men she left behind, not in the ceasing of her own existence. This, in turn, perpetuates the Female Victimisation in discourse on filmic depictions of the genocide.

Conversely, Martine is presented as a more rounded out character than Jeanne, and her storyline in the film is not solely centred around Augustin. Through Martine and Honoré, Peck explores the differing justice systems employed after the Genocide, with Martine participating in a Gacaca tribunal, and Honoré being prosecuted in a federal trial, but there is a narrative discrepancy in these portrayals, because Honoré is the central figure of his trial, and Martine is a participant in a larger community trial. This has the effect of metaphorically overshadowing women’s involvement in post-Genocide justice. One cannot overlook the symbolism in the contrast of Martine and Honoré’s respective roles; the narrative’s gender imbalance is significantly enhanced by their displayed involvement in the justice systems.

In Holmes’s discussions of the Genocide’s gendered narratives, she notes how factors affecting a woman’s engagement with and experience of genocide, such as ethnicity, class, political/religious beliefs, are flattened out in the context of the Tutsi Genocide, as there is a tendancy to subsume women’s stories into overarching “gendered narratives that posit them as victims” (82). This flat representation makes it harder for artists and audiences to pose questions about female characters - such as whether Jeanne would have been a complicit bystander if she was spared, or whether she would have been burdened by survivor’s guilt - because she is killed off before any complexities of her character are articulated. Moreover, there is an expectation that an audience’s only response to the representation of women involved in the Genocide should be one of pity, but in conforming to these expectations, we overlook the crucial roles of other forms of Female Witnesses to the genocide, most notably Hutu women who participated in the killings of Tutsis.

Peck’s film is a commendable Artistic Testimony of the Genocide, but in excluding female narratives, it is also inadequate in it’s representation. Even in the present day, there is a high demand for films depicting mass atrocities (Bostock, 2019). Sometimes in April is undoubtedly a contributing factor in this increasing demand, by virtue of its emotional realism and complex, informed storytelling. Compared to other filmic depictions of the Genocide, Peck’s work has also rightly become the ‘gold standard’ for Tutsi Genocide filmic representation. For this reason, current audiences, film critics, and directors have a responsibility to mention Peck’s shortcomings, and to ensure that in future depictions the varied perspectives of Rwandan women are presented. Exclusive focus on the Female victim results in Revisionist accounts of the genocide, which further the cycle of Victimology by turning women into victims of Historical Epistemicide.

Photographic Depiction of Rwandan Women

While films are generally assumed to be overdramatised and exaggerated for entertainment purposes, photographic testimonies are held closer to realism, regardless of whether or not they, too, contain fictionalised elements. One of the most notable photography collections on the Genocide is RWANDA (1999) by Raymond Depardon. Currently, 23 photos from this series are publicly available on ARTSTOR, in which 14 women, 8 men, and 10 children are depicted. Given the criticisms directed towards Sometimes in April and its lack of inclusion of female narratives, one may thus assume that this male:female ratio excuses Depardon’s work from this paper’s Historical Revisionism criticisms, but I argue that these photos are insufficient representations of the female experience, as they flatten women into “mother” or “victim”1 archetypes, thus perpetuating Victimological notions of innocence and helplessness. A majority of the images capture forlorn female subjects, while the few happy women are captured alongside their children, which conveys a correlation between these women’s proximity to children and their perceived happiness. This further flattens out the portrayals of women. Moreover, several photos in the collection subsume the “victim” and “mother” archetypes by depicting forlorn women with their children. Contrastingly, a large percentage of the men featured in Depardon’s collection are captured interacting with age-mates, or in a state of “doing”2 (ie. with a bicycle, on a walk, using/holding a tool), where any photos of women “doing” are few compared to the total depictions of women, and the only photos of women with agemates are with other men.

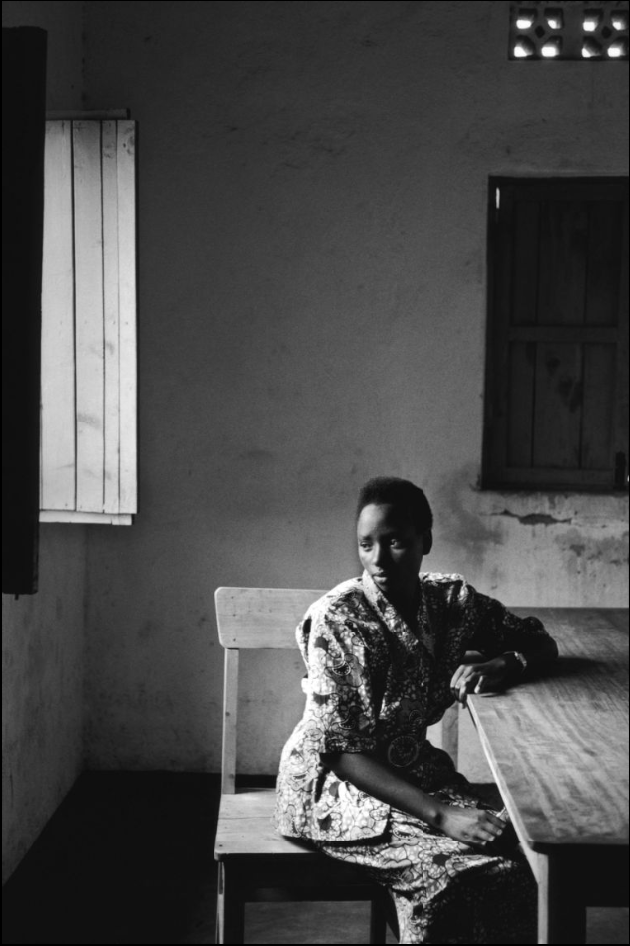

As a general depiction of the Rwandan post-Genocide sentiments, Depardon excells at crafting emotional imagery that reflects the country’s grief. His use of high contrast lighting and a monochrome palette give his photographs the appropriate amount of seriousness. As his work aims to leave it's viewers with an understanding of the gravity of the Genocide, and the pain of recovery, his shots tend to include a lot of negative space, possibly symbolising isolation. To discuss his artistic (and ethical) choices, I will analyse a particularly compelling photo from his collection, the portrait of a young female Tutsi survivor:

(Depardon, “Jeannette AYINKAMIYE”, August 1999)

Ayinkamiye, is aged 17 in the picture, and is simply described as a “farmer, and seamstress, a Tutsi survivor” in Depardon’s image description. This image was chosen to highlight the depth of symbolism and covert storytelling within the overt Victimology displayed. Through this analysis, I seek to highlight how nuanced and complex storytelling within Artistic Testimonies has the potential for use in a wider variety of scenarios.

The first observation is Depardon’s image composition. His use of negative space is accentuated by the image’s unusually long dimensions, and Ayikamiye’s placement in the bottom right corner of the frame, which serves to convey an atmosphere of loneliness. This atmosphere is enhanced by the minimalism of the setting (bare walls, empty table), and Ayinkamiye’s facial expression. Regarding Ayinkamiye’s pose in the photo, Depardon does not mention whether or not he instructed her to sit in the position he captures her in, but one could speculate that the photo is somewhat staged. This would then raise ethical concerns regarding Depardon’s responsibility as a photojournalist to state which images are candid, and which were set up with subjects posing. In excluding this information, Depardon is able to blur fiction and non-fiction in his work, which enables him to perpetuate gendered narratives in his collection. This collection, if taken at face value, would then be a Revisionist representation of post-Genocide Rwanda, one riddled with the etic perspectives of the male photographer which may bias the story his work tells. Furthermore, if only some of these photos are staged, but are presented amongst several genuinely candid shots, it is harder to determine what should be used as a reliable source of historical testimony, and what is more of an aesthetic representation.

Regardless of the implicit biases behind the shot, and the grave ethical considerations around it's usage, the photo remains a very effective emotional portrayal of a survivor’s experience in the years following the Genocide. In isolation, photos like Ayinkamiye’s portrait, can serve as needed representations of the tragedy for a global audience, but in the larger body of work, these types of images are not balanced out by more varied scenarios, such as shots of groups of women interacting to match the photos of men interacting. This imbalance therefore spotlights Victimised witnesses, and overshadows bystanders, perpetrators, or just emotionally conflicted survivors. Conversely, there is no representation of fatherhood in the available photos, despite the fact that numerous families were left motherless from the conflict; there is a hypocrisy to Victimological narratives that centre around women being killed/maimed/traumatised, but then fail to adequately touch upon the families left in their wake. In the case of Sometimes in April, where Augustin is left without a wife, she is ‘replaced’ by Martine, countering the “finality” of loneliness captured in Depardon’s piece, thus removing any possibility for lingering victimhood in the male narrative.

Both Depardon and Peck are incredibly talented artists, and the praise for these visual testimonies is rightly deserved, as they are profoundly skillful in their use of composition, their framing of subjects, their control of moodier colour and lighting to reflect Rwanda’s emotional atmosphere. Both artists also manage to maintain considerable depth and nuance in their work while ensuring their messages are still accessible to audiences, a valuable skill when presenting the emotional turmoil of Genocide to an audience who have not experienced it. As both works are created for Western audiences, it must also be assumed the artists do, to some extent, pander their messages to Western expectations and the normative African discourse.

Ultimately, although these artists are exceptionally talented, and have captured the trauma suffered by these witnesses with remarkable sensitivity, their influential bodies of work will serve as Historically Revisionist Testimonies that flatten female experiences and undermine women’s crucial voices in historical narratives.

The Female Witness to The Tutsi Genocide

In the Journal of Genocide Research, several noteworthy articles explore the roles women played in the Genocide. I will discuss one published in the journal’s very first volume, to demonstrate that there has been an understanding amongst Intellectual Witnesses of the varied modes of women’s engagement in this Genocide. “Gender and Genocide in Rwanda: Women as agents and objects of Genocide” (Sharlach, 1999), outlines the roles Hutu women played in politically orchestrating the genocide (Sharlach 387), as well as actively perpetuating it through participating in the killing of Tutsi women and Children (389), but also explores the roles Tutsi women played in genocide resistance. As Sharlach puts it: "In 1994 Rwanda, a woman's loyalty to her ethnic group almost always overrode any sense of sisterhood to women of the other major ethnic group. The case of the Rwandan genocide underscores the need for practitioner of women's studies not to overlook ethnic politics when examining violence against women." (388)

It is evident how this placement of loyalty contrasts the universalist victimisation of Rwandan women that Holmes addresses, and an acknowledgement of this reduced sense of sisterhood challenges the normative discourse that assumes African women to all be in agreement, and thus all at the same level of innocence. I call this universalist, as any interpretations of women’s roles in the genocide which create a dichotomy of ‘divided men and united women’ reduces the female experience of genocide by implying that women were merely collateral damage in a conflict perpetuated solely by Hutu men. Gender and ethnicity are different axes of identity which uniquely affect each individual. Acknowledging this allows artists and audiences to deconstruct Victimological frameworks that lump the women engaged in this genocide into one category of ‘female victim’.

A truly all-encompassing representation of women’s engagement in the Tutsi Genocide would extend beyond portrayals of the ‘victim’ and ‘emotionally compromised survivor’, and would include perspectives from complicit bystanders, female 1.5 Generation witnesses, and female perpetrators of genocide, and women involved in the resistance. Furthermore, artistic representation could benefit greatly from referencing the works of Female Intellectual Witnesses.

Conclusion

It would be very challenging to attempt to portray all of the nuances of women’s engagement in the genocide, but this should not excuse the normative discourse of the female African victim. Filmic and photographic explorations of genocide are tools that influence collective understandings of these events, and can be used to spark necessary social/political change, but in subscribing to Victimology, and perpetuating Historical Revisionism, these works maintain the status quo, thus feeding into the continuous Epistemicide of African women.

There is much to be said for an Artistic testimony that would depict Hutu women spreading hatred and anti-female propaganda through the RTLM, or a woman (Tutsi or Hutu) married to a Hutu soldier who becomes complicit in the torture, rape, and murdering of other women she once knew. These storylines would be just as emotionally captivating as the ones Peck and Depardon explore in their works.

Bibliography

- Bostock, Mark. “Implicit Criminologies in the Filmic Representations of Genocide.” Representing the Experience of War and Atrocity: Interdisciplinary Explorations in Visual Criminology, Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 123‑151.

- Holmes, Georgina. Women and War in Rwanda: Gender, Media and the Representation of Genocide. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013.

- Katila, Anna. "Unearthing Ambiguities: Post-Genocide Justice in Raoul Peck’s Sometimes in April and the ICTR case Nahimana et al." International Journal of Transitional Justice 15.2 (2021): 332-350.

- Sharlach, Lisa. "Gender and genocide in Rwanda: Women as agents and objects of Genocide." Journal of Genocide Research 1.3 (1999): 387-399.

- Peck, Raoul, director. Sometimes in April. Home Box Office, 2005.

- Raymond Depardon. “RWANDA. Nyamata. Jeannette AYINKAMIYE, 17 Years Old, Farmer and Seamstress, a Tutsi Survivor. August 1999”, RWANDA 1999, RWANDA Collection. Pictures Taken for the Book Dans Le Nu de La Vie. Récits Des Marais Rwandais, by Jean Hatzfeld, Ed. Du Seuil, 2000. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.9849486. JSTOR.

- Raymond Depardon. “RWANDA. Bugesera Region. Nyamata. In 1994 Rwanda Was the Theatre of a Massive Genocide Perpetrated by the Hutu Ethnic Group against the Tutsis. Following the Decision of the Hutu-Dominated Government to Form a Coalition Government with the Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in 1992, the Hutu Extremists Killed the President of Rwanda HABYARIMANA, and an Estimated 200,000-500,000 Civilians, Most of Them Tutsi. In Response, the RPF Resumed Its Military Campaign. Hundreds of Thousands of People,

Footnotes

-

“Victim” in this sense does not refer to a individuals killed in the Genocide, but instead refers to scarred survivors; victims of trauma. The scarred survivor falls under Holmes’ notions of Victimology. “Mother”, too, is part of the normative discourse around African women that Holmes identifies, as it is the default character in any testimony aiming to elicit emotional responses from Western audiences. The latter archetype is based in the neo-colonial, patriarchal perception of African women that needs to justify their existence via their ‘contributions to society’ (ie. bearing children), as it has not yet granted African women permission to exist validly by virtue of being human. ↩

-

There are photos of women holding tools, too, but this analysis focuses more on the number of photos of men holding “doing”/holding tools out of the total number of photos of men, as compared to the number of photos of women “doing”/holding tools, out of the total number of photos with women. ↩